The breakfast of the Tarantata

Women, rituals, and the magic of rural Puglia

The countryside is one of the recurring themes in my writing and in my culinary research. It’s an essential lens through which to understand Puglia — a complex, multifaceted, and in many ways mysterious region.

It’s within this scorched, symbolic landscape that one of Southern Italy’s most enigmatic phenomena took shape: “tarantismo”.

Mystery, ritual, dance, and womanhood intertwine uniquely in this phenomenon, whose name comes from the “taranta”, an unidentified spider said to have thrived in Salento.

(A tarantata outside the Chapel of Saint Paul in Galatina. Picture from the exhibit “Viaggi nelle terre del rimorso. Immagini del tarantismo”, by Paolo Pisanelli and Francesco Maggiore. Castel of Corigliano)

According to popular belief — documented since the Middle Ages — “tarantismo” was a strange illness caused by the bite of the “taranta”.

Those “bitten” were mostly women: peasant laborers who worked long hours in the fields of tobacco and wheat in Salento, the southernmost part of Puglia.

Legend has it that among the leaves of the tobacco plants or between the wheat stalks, imaginary spiders hid and bit the women around the hips — a symbolic wound often linked to repressed sexuality and female oppression (as the traditional song “Santu Paulu” also recalls).

The “tarantate” — the “bitten” women — suffered from melancholy, depression, muscle pain, and exhaustion.

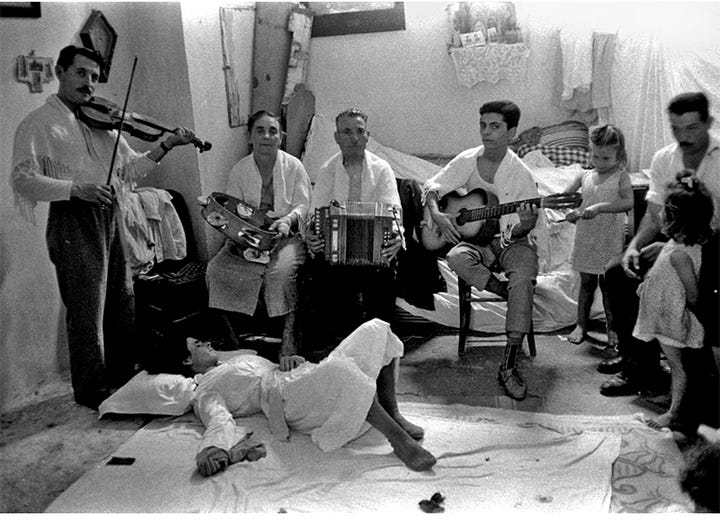

(A tarantata in her house. Picture from the exhibit “Viaggi nelle terre del rimorso. Immagini del tarantismo”, by Paolo Pisanelli and Francesco Maggiore. Castel of Corigliano)

Over time, some physicians began interpreting “tarantismo” as a form of female hysteria or mental illness — a psychological response to the hardships of peasant women’s lives.

Exploited under the sun for endless hours, lowest on the social ladder, often victims of abuse and sometimes even sexual violence (as suggested in the song “Fimmene fimmene”), these women carried a deep, unspoken pain.

To agricultural labor was added domestic work and childcare — a constant emotional fatigue, far more devastating than any spider’s bite.

Traditionally, the women were “healed” at home through a complex musical ritual — an ancient form of therapy through dance.

Accompanied by tambourines, violins, accordions, and harmonicas, the women would enter a trance and begin a frantic dance that could last for days.

Watched over by their families, they crawled, arched their backs, shook their heads, and mimicked the spider’s movements.

By dancing, they sweated out the poison — freeing themselves from the evil within.

The ritual ended when the woman, finally standing, stomped the imaginary spider under her feet — a gesture of liberation.

According to the anthropologist Ernesto De Martino, who studied this phenomenon extensively in his seminal book “La terra del rimorso” (The land of remorse*), “tarantismo” was a complex system of beliefs and rituals deeply rooted in rural Southern culture.

Over time, the Catholic Church sought to channel these expressions of ecstasy into the framework of faith.

To the Church, the musical exorcism appeared as a frenzied, pagan rite — something to be viewed with suspicion.

To avoid excommunication and social disgrace, the “tarantata” had to repeat the healing ritual she had performed at home, this time in the Chapel of Saint Paul in Galatina, the saint who protected crawling and venomous creatures.

Here, she would perform a short version of the dance-exorcism; at its climax, she would collapse to the ground as the spider symbolically left her body — a sign that Saint Paul had granted her grace.

The rite ended with the woman drinking water from the chapel’s well.

(Maria from Nardò drinking the well water. Picture by Franco Pinna. From the book “La terra del rimorso” by Ernesto De Martino)

When I visited Galatina, Gianfranco Conese, the chapel’s caretaker, told me that this water was not only dirty but also foul-smelling and sulfurous, with small water snakes sometimes swimming in it.

It’s no coincidence that the ritual often concluded with the woman vomiting the water — a final act of expulsion, the body’s way of rejecting the evil that had tormented her.

(The well of Saint Paul in Galatina)

Mr. Conese also showed me some photographs from the 1960s that caught my attention.

They depicted what was known as “la colazione della guarita” — “the breakfast of the healed woman” — a symbolic return to everyday life after days of trance and fasting.

In the photos, taken just outside the church, women sit eating simple, restorative foods to regain their strength after the exhausting ritual.

In one image, a woman appears to be eating a “frisella” — Puglia’s traditional twice-baked bread ring, made with wheat or barley flour, designed to last for months.

Before eating, it’s dipped briefly in water and seasoned with olive oil, salt, and tomato (or other vegetables).

(One of the pictures Mr. Conese showed me in Saint Paul chapel. The breakfast of the healed woman)

In another photo, two women eat warm soup from a bowl. Beside them sits an earthenware pot, likely used to cook legumes in a wood-fired oven — the backbone of the peasant diet of the 1960s.

On the ground, two bottles of wine, probably Negroamaro — the most representative grape of Salento.

An energizing, comforting breakfast, necessary after such an intense physical and spiritual ordeal.

(The second picture Mr. Conese showed me in Saint Paul chapel)

From the 1970s onwards, the magical, spiritual, and rural dimensions of “tarantismo” gradually faded, absorbed into Catholic ritual.

Today in Galatina, on June 29th — the feast day of Saint Paul — the connection between the saint and the “taranta” is still celebrated, but mostly as a religious event marked by processions and Mass.

What remains alive is the music: the “pizzica”, the dance of the “tarante”, still played during summer festivals across the 96 towns of the province of Lecce — a living echo of an ancient, ancestral rhythm.

It’s the heartbeat of the South, still pulsing in the nights of Puglia.

Two places to note

If you visit Galatina, after seeing the Chapel of Saint Paul (check the opening hours at the tourist info point), I recommend tasting some of the city’s traditional specialties.

Galatina is the birthplace of the “pasticciotto”, a pastry made with shortcrust dough (traditionally made with lard instead of butter), filled with custard and baked until golden.

It’s said to have been invented in 1745 at Pasticceria Ascalone, founded in 1740 and still open in the heart of the old town.

Pasticciotti

Among the local baked goods, don’t miss the “pizzi” and “rustico leccese”, which I tasted at Staglio Panificati.

“Pizzi” are small, rustic rolls made from durum wheat and flavored with tomato, onions, and black olives; “rustici leccesi” are delicate puff pastry discs filled with tomato, mozzarella, and béchamel — glossy, flaky, and irresistible.

Fantasticamente emozionate!

Grazie mille, Flavia🤩